The Friday Alaska Landmine column: Why we oppose the Cook Inlet gas subsidy bills

A recent slide offered by the Department of Natural Resources to support state subsidies to Cook Inlet gas producers actually proves the opposite - that the subsidies aren't needed

Over the last few weeks, we have written several columns discussing current Cook Inlet gas issues on these pages. We have taken a consistent position on those issues, opposing the use of subsidies both because we believe the market can handle the problem and out of concern over the adverse impacts that would arise from the subsidies.

As covered in last week’s edition of Petroleum News Alaska (“Proposed legislation for encouraging new gas development reaches House Finance”), three bills currently moving in the Legislature are designed to subsidize Cook Inlet gas: HB 257, which is designed to make state-owned seismic data available free of charge to certain persons, including “anyone involved in Alaska oil, gas or minerals exploration”; HB 223, which would “eliminate state royalties for natural gas production” from certain Cook Inlet projects and other things; and HB 387, which would provide “a state tax credit to any entity that installs a jack-up rig in Cook Inlet.” At the time we are writing this week’s column, all three are currently pending before the House Finance Committee.

In addition, HB 388, which would establish a Cook Inlet reserve-based lending fund in the Alaska Energy Authority (AEA), is also pending before the same Committee. Under the proposed statute, AEA would be authorized to provide “reserve-based lending” to Cook Inlet producers at an interest rate “less than the cost of funds to the authority,” in other words, at a subsidized rate.

We oppose these bills, first, because we believe the subsidies they reflect aren’t necessary.

Earlier this week, Derek Nottingham, the Director of the Department of Natural Resources Division of Oil & Gas (DNR), testified before the House Finance Committee on HB 223. While the slide deck he used with his testimony purported to support the need for HB 223 and, through it, the other subsidies, we believe it demonstrates the exact reverse. Here is the key slide:

On the right-hand side, the slide shows the economic impact of waiving state royalties on the estimated cost to producers of developing the supply. Using the numbers on the slide, waiving state royalties would reduce the cost from $12.26/Mcf to $10.48/Mcf. According to Nottingham’s testimony, doing so would change the development economics of certain Cook Inlet projects sufficiently to make producers invest in and develop projects they otherwise haven’t to date.

But consistent with our view developed in an earlier column, our take away from that slide is much different. To us, it says that if Cook Inlet buyers raised the price they were offering to $12.26/Mcf, Cook Inlet producers would be in the same place with the same economic incentives to develop additional supplies. The only difference would be that the market participants – Cook Inlet purchasers – would provide the needed incentives rather than state subsidies.

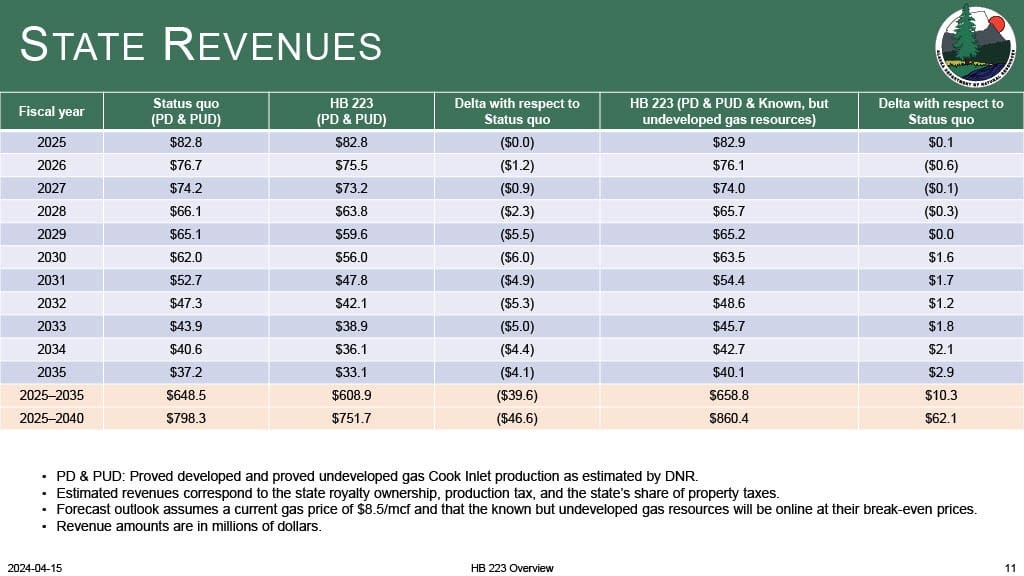

In a subsequent slide included in the appendices to his presentation, Nottingham claims to show that, by subsidizing royalty, the state potentially could come out ahead. If the subsidies resulted in the development of additional supplies beyond the “status quo,” the production and property taxes received on the additional production could increase state revenues by more than the losses resulting from subsidies on the “status quo” volumes.

But that doesn’t prove the subsidies are beneficial. The state would be in an even better position if, instead of the state subsidizing the result, the Cook Inlet buyers paid the market price for the volumes. Not only would the state avoid the projected $46.6 million loss on the “status quo” volumes, but it would come out even further ahead by recovering royalty also on the additional “known, but undeveloped gas resources” the chart projects could be developed. Instead of the $860.4 million in revenue projected on the chart, total state revenue would likely be closer to $1 billion over the period.

As we explained in our earlier column on the issue, given these factors, we believe there is some other reason(s) behind the proposed legislation. Instead of subsidizing producers, perhaps the intent of the legislation is to subsidize Cook Inlet gas purchasers, providing them with the ability to buy a product that actually costs “$12.26/Mcf” to develop at a discount for only “$10.48/Mcf.” Doing so benefits them by enabling them to retain customer demand they otherwise might lose at the higher price and to avoid tighter scrutiny from the Regulatory Commission of Alaska (RCA), the regulatory body that oversees their operations and prices.

The reduced price also might be to mask the lack of competitiveness of Cook Inlet supplies against those available from other markets. As we explained in another earlier column, in last year’s “Alaska Utilities Working Group Phase I Assessment: Cook Inlet Gas Supply Project” (July 2023), the most recent, detailed, publicly available study on the issue, the midpoint of the projected cost of imported LNG is significantly lower than that of additional Cook Inlet production, leading directly to the conclusion that Cook Inlet purchasers should be pursuing imported LNG rather than additional Cook Inlet production.

The subsidies help obscure that result by artificially lowering the price of Cook Inlet production to purchasers, leading some to believe that the cost of Cook Inlet production remains competitive against those from other sources of supply when, in fact, it does not.

But we don’t oppose the subsidies only because we believe the market could better handle the decision instead or because we believe the proponents are hiding the ball about who they are attempting to benefit. We also oppose them because we believe the use of subsidies, in this case, will be harmful.

The first reason we believe they are harmful is that there is a significant mismatch between who will pay for the subsidies and who will benefit from them. In the state’s current fiscal environment, the subsidies will be paid for through additional cuts in the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD), the state’s current marginal source of revenue. As we have explained in previous columns, that means the costs will be borne largely by middle and lower-income Alaska families statewide. Among Alaska families, those in the upper-income bracket (the “top 20%”) will contribute only a trivial share toward the costs.

Yet, because they are direct (consume gas) and indirect (consume gas-generated electricity) consumers of Cook Inlet gas, it is undeniable that top 20% Alaska families in Southcentral and otherwise along the Railbelt will also be significant beneficiaries of the subsidies. As is the case generally, by creating the subsidies and using PFD cuts to fund them, middle and lower-income Alaska families perversely will be paying more to make the lives of those in the top 20% even better. The top 20% will receive a significant benefit from heavily subsidized gas service but pay only a trivial share of the costs.

It will grow the income gap, which is at the heart of many of Alaska’s problems, not reduce or even keep it stable.

Not only that, as Professor Matthew Berman of the University of Alaska – Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) has generally explained elsewhere, using PFD cuts to fund the subsidies will also push additional Alaska families nearer to or below the state’s poverty line. Cook Inlet producers and purchasers will benefit at the expense of many Alaska families who are pushed further down the economic ladder. The state also will incur additional costs in providing support to the artificial increase in the number of Alaska families at or near the poverty line.

As we’ve explained in a previous column, the subsidies also will adversely impact the incentives and costs in adjacent markets. For example, by artificially lowering the cost of gas and electricity, the subsidies also will artificially lower the economic incentive for increased weatherization and other conservation measures. This, in turn, will lead to maintaining higher demand for those products at the very time we should be seeking to reduce it. By lowering the private sector incentive to do so, the subsidies will also increase the costs to the state if it attempts to accomplish demand reductions through weatherization and other conservation measures through subsidies also in that market.

The same perverse effect also will occur in the renewables market. By artificially lowering the cost of gas-generated electricity, the subsidies also will artificially lower the economic incentive for the development of additional renewables. As in the weatherization and conservation markets, this, in turn, also will lead to maintaining demand for gas-fired generation at the very time we should be seeking to reduce it. And similarly, by lowering the private sector incentive to do so, the subsidies will also increase the costs to the state if it nevertheless attempts to incentivize the development of additional renewables through subsidies in that market.

In short, the impact of subsidizing the Cook Inlet gas market is not limited only to that market. Because of the source of funds used to pay for the subsidies, the subsidies also will disproportionately reduce the income of middle and lower-income Alaska families statewide, as well as increase poverty levels and, through that, increase the costs to the state of supporting those at or near that income level. The subsidies also will adversely affect the adjacent conservation and renewables markets, and if the state tries to overcome that through increased subsidies in those markets, also state spending levels in those markets, triggering even further cuts in PFDs and expanding the adverse impacts of that even further.

To us, there is no good reason to start sliding down that very slippery slope. As the slides from the DNR presentation themselves help demonstrate, the so-called “Cook Inlet gas crisis” is a situation the market can easily handle. We should let the market do exactly that and, at least in this instance – as the very same Republicans pushing the subsidies here often remind us should be done in other markets – remove the state from the subsidy business.