The Friday Alaska Landmine column: What the latest state-level IRS data tells us

While some claim they are concerned about net outmigration, the income gap between middle-income Alaska families and those in the Top 25% is continuing to grow, and PFD cuts are making it even worse

About a year ago, we took a look on these pages at what the then-most recent state-level data from the Internal Revenue Service told us about Alaska’s income.

In this column, we are updating that look using data from the last five years of state-level Internal Revenue Service (IRS) reports, ending with the most recent available, for tax year 2021.

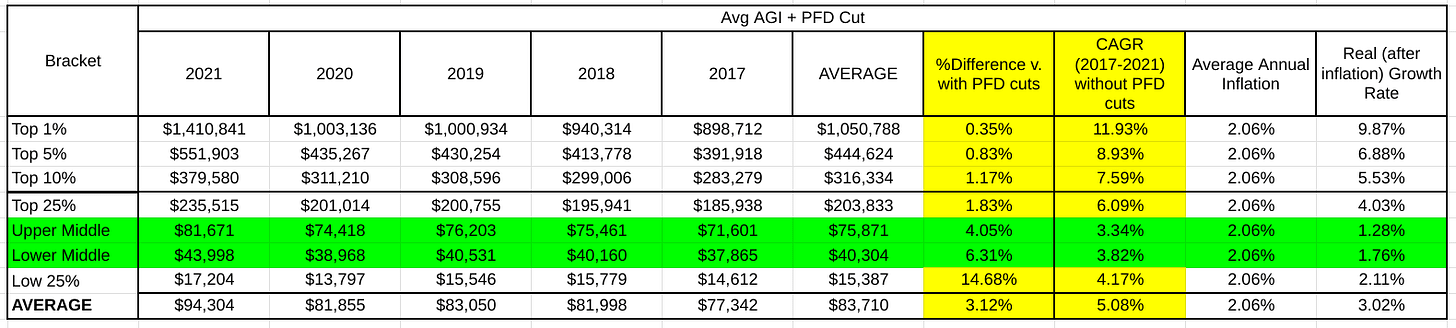

As a starting point, here is the average adjusted gross income (AGI) for each of the last five years for which data is available, broken down by the income brackets used by the IRS in presenting the data. Because they sometimes get lost in the discussion, we have highlighted the data related to the middle-class income brackets in green.

In reviewing the chart, recall that the state-level IRS data is broken down into quartiles (25% increments) rather than the quintiles (20% increments) the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) and some other sources use. We define the middle class as the 50% of households falling into the middle two quartiles: the second 25% and the third 25%.

We define the first quartile as the Top 25% and the fourth quartile as the Low 25%. The top three rows – the Top 1%, Top 5%, and Top 10% – are subsets of the Top 25%.

When discussing this data, some occasionally ask about the range for each income bracket. The IRS includes the floor for each bracket as part of its annual analysis. Here are the floors and the average for each bracket for 2021. Within the quartiles, the floor for each bracket is the ceiling for the previous one. For example, the floor for the Lower Middle-Income bracket is $27,668, and the ceiling is $55,512, the floor for the Upper Middle-Income bracket. There are no ceilings within the Top 25% bracket. In other words, the range for the Top 25%, Top 10%, Top 5%, and Top 1% is simply the floor “and up.”

As the first chart shows, average income has increased over the period, though unevenly. For example, in COVID-affected 2020, the average AGI for those in the top 25% increased some but fell for everyone else.

The following chart shows the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the period by income bracket. As is apparent, the annual income growth rate for those in the top 25% far exceeds those in the remainder of the brackets. Using the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index measure for “urban Alaska,” average annual inflation averaged 2.06% over the period. While the average compound yearly income growth rate in all quartiles exceeded that – in other words, income growth in all brackets exceeded inflation – the real (after inflation) growth rate for those in the top 25% income bracket was substantially higher than for the remainder.

While the compound annual real income growth rate of those in the top 25% exceeded 3.5% and within the top 10% exceeded 5%, the real growth rate of those in the middle-income brackets (as well as those in the low 25%) were at 1% or below. The net effect is that the already significant income gap between Alaska families widened during the period.

We can also use the data to show the impact of cuts in the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) on Alaska households over the period. The IRS data allows us to calculate the average household size in each bracket. By multiplying the amount of the PFD cut by the size of the average household, we can determine the income level the average household in each bracket would have received had the PFD not been cut.

As the following chart shows, the use of PFD cuts to fund the government during the period widened the gap between the income brackets even further. For example, without PFD cuts, the average income for those in the second quartile would have been 4.1% higher, 6.3% higher for those in the third quartile, and 14.7% higher for those in the Low 25% quartile.

While there still would have been a natural disparity in the growth rate between those in the top 25% and those in the other brackets, it would have been less, narrowing the income gap between Alaska families compared to the larger, government-driven disparity created by using PFD cuts.

Of course, assuming the same level of spending, state government would have needed to tap alternative sources of revenue in the absence of using PFD cuts. Adjustments in oil taxes might have covered some of the difference, but the IRS data enables us to look at the impact if the legislature had used other forms of revenue measures instead of PFD cuts.

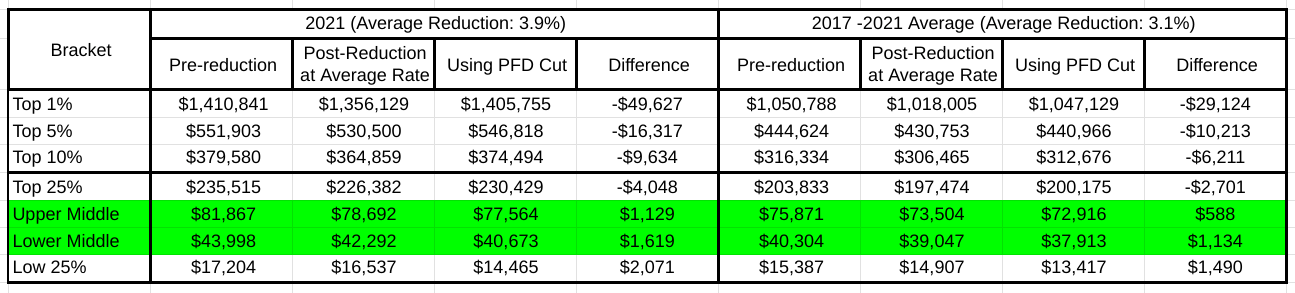

For 2021, using PFD cuts reduced average Alaska household income, adjusted for the current law (statutory) PFD, by 3.9%. Over the full period, using PFD cuts reduced average Alaska household income by 3.1%. This would have been the impact had each income bracket been reduced by the average rate to pay for government rather than the highly regressive rates resulting from using PFD cuts.

While those in the Top 25% would have contributed more dollars using the average rate than PFD cuts, because all brackets contribute at the same rate, they would have contributed no more as a share of income than those in any other bracket. By leveling the take at the average rate, the remaining 75% of Alaska households – those in the Upper and Lower Middle-Income brackets as well as those in the Low 25% – would have seen real increases in income compared to using PFD cuts, helping to close the income gap.

The negative amounts in the previous chart for those in the Top 25% show the benefit to them and the cost to the other 75% of Alaska families of using PFD cuts compared to an average rate approach. The same amount of Alaska income goes to government either way, but using PFD cuts enables the Top 25% to avoid taxes they would otherwise incur if they were required to contribute toward government costs at the same average rate as the other 75% of Alaska families.

Here’s the impact, which is stated as a percentage of income.

In tax year 2021, those in the Top 25% increased their income by 1.67% due to the legislature’s decision to use PFD cuts to pay for government costs instead of an average rate approach. Within the Top 25%, those in the Top 10% increased their income by 2.52%, those in the Top 5% by 2.95%, and those in the Top 1% by 3.52%.

That increase in income among those in the Top 25% was paid for by reductions in income among the remaining 75% of Alaska households. Those in the Upper Middle-Income bracket received 1.67% less income, those in the Lower Middle-Income bracket received 4.30% less income, and those in the Low 25% received 15.05% less income using PFD cuts to fund the increased income enjoyed by those in the Top 20%.

Put bluntly, using PFD cuts, 75% of Alaska households paid more than the average rate – what in many contexts would be called a subsidy – so those in the Top 25% could pay less.

Throughout this discussion, we have highlighted the numbers applicable to those in the middle-income brackets for a reason.

Often, during the discussion about these issues, many highlight the impact of using PFD cuts as a revenue source on those in the low-income brackets. While those cuts may be more significant as a percentage of income, the point we want to make here is that, directionally, the same adverse impact also affects middle-income families.

Substantial concerns have recently been expressed about Alaska’s problems attracting and retaining working-age families. As we explained in a previous column using IRS data, those issues are significant among middle-income working-age families.

Focusing on the data relevant to middle-income families demonstrates that, by using PFD cuts to fund government, Alaska is making it more expensive for those families to remain in the state – increasing their cost of living – compared to other revenue alternatives. Those genuinely concerned about the migration issue should pay attention. The choices the legislature is making about raising revenue are worsening the working-age migration problem.