The Friday Alaska Landmine column: An interim 2024 state revenue and budget update

Projected revenues are the same, but spending - and with them, deficits - are up since the mid-session Spring Revenue Forecast

Over the past two years, we have used columns during the summer and fall to fill gaps in the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) regular cycle of state revenue forecasts. As we said when we began the practice:

The Department of Revenue publishes two formal revenue updates each fiscal year. The first is the detailed Fall Revenue Sources Book, published in December in connection with the submission of the governor’s budget. The second is the Spring Revenue Forecast, published three months later, in March, as the Legislature comes to grips with the annual budget.

While the Department also publishes occasional updates, those have a more limited circulation and aren’t as widely used as a public source of data for changes in the state’s fiscal outlook.

So, as part of our Alaska Landmine “Chart of the Week” series, we are going to attempt to help fill in the 9-month gap between the Fall and Spring forecasts with two additional three-month looks in mid-June and mid-September.

This year, we are modifying that schedule to publish only one interim look — this one in late August, midway between the state’s official looks in March and December. An earlier update hasn’t been particularly urgent since, to this point, there hasn’t been much change in the revenue outlook since the Spring Revenue Forecast. Doing the update in late August also provides an updated baseline for candidates and voters to use as we move into the general election cycle.

As in the previous updates, we review the outlook separately for revenues, spending, and net.

Revenues. There are two significant drivers of state revenues under current law: oil revenues (which, in turn, are a combination of prices and production levels) and the portion of Permanent Fund earnings that are available for state government under current law (i.e., the percent of market value (POMV) draw remaining after deducting current law Permanent Fund Dividends (PFD)).

To this point, the outlook for oil prices has mostly stayed the same as in the Spring Revenue Forecast. Those who follow us on our Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn pages know that we update the Alaska North Slope (ANS) oil price outlook weekly on Friday mornings based on the most recent prices in the futures markets, adjusted for an estimate of the differentials between Brent (the commodity covered in the futures market) and ANS. We analyze these differences weekly and monthly.

In the same Friday morning charts, we also update the impact of those oil price projections on traditional revenues, using the price sensitivity analysis prepared by the Department of Revenue as part of its regular revenue forecast cycle.

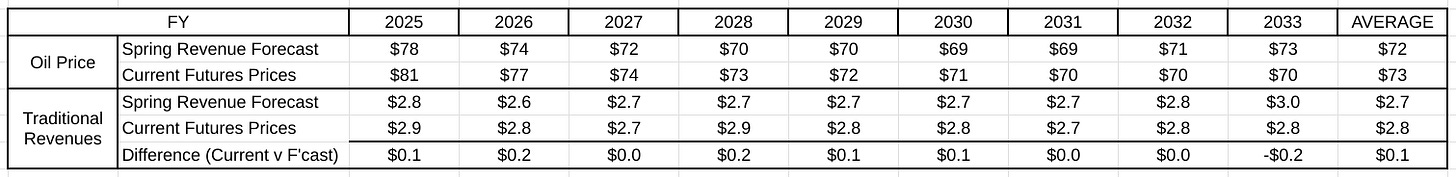

Here are the most recent projections as we write this week’s column, compared to those that were included in the Spring Revenue Forecast:

Both average oil prices and traditional revenues over the period remain within 5% of the projections made in the Spring Revenue Forecast. While current Fiscal Year 2025 production levels are running slightly lower than forecast, the difference isn’t material. Therefore, we have not adjusted the revenue forecast in this update for changes in production levels.

As with traditional revenues, the projected level of Permanent Fund earnings available for state government also has remained relatively stable since the Spring Revenue Forecast. We update our projections of those levels monthly using the most recent “History and Projections” report from the Permanent Fund Corporation.

Here are the most recent projections as we write this week’s column, compared to those that were included in the Spring Revenue Forecast:

While the projected level of the POMV draw is slightly higher over the forecast period than that included in the Spring Revenue Forecast, so is the projected level of PFDs under current law. The net effect is that the portion of the Permanent Fund earnings available for state government under current law remains unchanged.

Combining the two, here is the resulting total level of revenues projected over the period:

While there are some slight differences from year to year, those largely wash out when averaged over the full period. Currently, projected total revenues are within 3% of those projected at the time of the Spring Revenue Forecast. Total projected revenues over the period vary between $4.1 billion at the low end (FY 2026) and $4.6 billion at the high end (FY 2028), averaging $4.4 billion per year over the period taken as a whole.

In previous updates, we also included estimates of future revenues based on a 10-year rolling historical average of oil prices. As explained in a previous column, using the 10-year average is a much more robust fiscal approach than relying on future oil price projections, as the state currently does. To match those looks to the budget cycle, rather than adding to these updates, going forward, we will update the rolling 10-year analysis when the Department of Revenue publishes its Spring and Fall Revenue Forecasts

Spending. While projected spending levels are not included in the Department of Revenue’s Fall or Spring Revenue Forecasts, we include them in these updates to provide a complete overview of projected future budgets and deficits. In this update, we use the Legislative Finance Division’s (LegFin) estimates of unrestricted general fund spending levels included in its pre-session “Overview of the Governor’s [FY25 Budget] Request” to represent projected spending levels current as of the time of the Spring Revenue Forecast.

To represent currently projected spending levels, we use the FY 2025 unrestricted general fund spending levels approved in the enacted budget as reflected in LegFin’s July 16, 2024, FY 2025 “Fiscal Summary,” including the so-called “surplus” reserved for supplemental FY 2025 spending, escalated annually over the remaining period at the projected rate of inflation included in the Permanent Fund Corporation’s most recent “History and Projections” Report (2.5%).

Here are the results:

The chart reflects that the enacted FY 2025 budget is materially (8%) higher than the level projected in LFD’s pre-session overview. Because both starting levels are escalated at roughly the same rate, that relationship stays relatively constant.

As with a 10-year rolling historical average of oil prices, in previous updates, we have also included an analysis of the outstanding balance of the Constitutional Budget Reserve (CBR) and the additional levels required to pay back that balance in the near term over a defined period. As we explained in a previous column, the near-term payback of that balance is appropriate to ensure that the same generation that benefitted from borrowing from the CBR pays the amounts back. For the same reason as explained above for the 10-year rolling oil price averages, rather than continuing to add to these updates, going forward, we will include the CBR payback analysis when the Department of Revenue publishes its Spring and Fall Revenue Forecasts.

Net. While projected revenues have remained relatively constant since the Spring Revenue Forecast, projected spending levels have increased materially. As demonstrated in the following chart, the result is that the state appears to be facing significantly larger current law deficits over the period covered by the forecast than anticipated at the time of the Spring Revenue Forecast.

Due to the materially higher spending levels than projected at the time of the Spring Revenue Forecast, the state’s average deficits over the period are currently approximately $400 million per year – or about 30% – larger than anticipated then.

Here is the impact on PFDs, assuming the deficits continue to be covered entirely through PFD cuts over the period (the so-called “leftover PFD” approach). As noted above, we calculate and update projected current law PFDs monthly using the Permanent Fund Corporation’s most recent “History and Projections” Report:

The level of PFD cuts climbs over the period from $1.3 billion to $2.2 billion, the percent reduction in the current law PFD – or, using Professor Matthew Berman’s phrase, the “tax rate” on the PFD – climbs from 56% to nearly 77%, and the percent of the projected POMV draw distributed as PFDs drops from 28% in FY 2025 to approximately 14.5% by FY 2033.

As we have explained in previous columns, using PFD cuts to balance the budget is hugely regressive – it takes increasingly more from middle and lower-income Alaska families as a share of income than from those in the upper-income brackets. Indeed, Professor Berman concludes that the approach is “the most regressive tax ever proposed.”

Here is the projected average annual impact of those cuts by income bracket over the period if the deficits continue to be covered entirely through PFD cuts:

At an annual average of $1.7 billion, closing the deficit through PFD cuts reduces projected adjusted Alaska gross income over the period by approximately 4.8%. But the impact is hugely uneven across income brackets. The following chart compares the difference over the period by income bracket:

As a result of using PFD cuts to balance the budget, the average income of Alaska households in the lowest 20% income bracket is reduced by more than 20% more than the average Alaskan household, the income of those in the lower middle-income bracket is reduced by more than 7% more than the average, the income of those in the middle-income bracket is reduced by nearly 4% more, and the income of those in the upper middle-income bracket is reduced by almost 1% more.

On the other hand, by using PFD cuts to close the deficits, Alaska households in the top 20% realize savings (essentially, a tax cut paid for by overcollections from those in the middle and lower-income brackets) of 2% in income over the average impact, those in the top 5% savings of over 3% over the average impact, those in the top 1% savings of more than 4% over the average impact, and non-residents, who contribute nothing, retain 4.8% more income than if they were subject to the same average tax rate on their Alaska sourced income as everyone else.

Put another way, by using PFD cuts to close the deficit, those in the lowest 20% income bracket will see their income reduced by more than nine times more than those in the top 20%, those in the lower middle-income bracket will see their income reduced by more than four times than those in the top 20%, those in the middle-income bracket will see their income reduced by more than three times than those in the top 20%, and those in the upper middle-income bracket will see their income reduced by two times more than those in the top 20%.

On the other hand, those in the top 5% will see their income reduced by only half as much as those in the top 20% overall, and those in the top 1% will see their income reduced by only a quarter of those in the top 20% overall. Non-residents who contribute nothing will retain all their Alaska-sourced income, while those in the top 20% will see theirs reduced by 2.8%.

What it means. The update’s plain meaning is clear: Due to a material increase in spending this past session, the state budget is sinking deeper and deeper into the red. Revenues aren’t rising to offset the increased spending; at best, they stay flat. Rather than confronting the resulting deficits transparently and closing them equitably, the Legislature is instead relying on the growing diversion of PFDs to mask the effect.

By using PFD cuts to close the resulting gap, middle and lower-income Alaska households – which combined, are 80% of Alaska families – are growing poorer than all Alaskan households on average, while those in the top 20% and non-residents are growing richer than the average at rates far greater than those resulting from the fiscal approaches used in other states. If not driving, the disparity certainly contributes to the outmigration of working-age Alaska families. The numbers are in plain sight. Those who ignore the impacts are just turning a blind eye to a deteriorating situation.