The Friday Alaska Landmine column: Where this Legislature is leading Alaska

Fiscally, Alaska is on track to "remain a tax haven for non-residents and those in the top 20%, but the most-regressive-in-the-nation sinkhole for the remaining 80% of Alaska families"

Following the release late last year of Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) proposed Fiscal Year 2025 (FY25) budget, we published two columns looking at both its current and long-term impact over the period covered by the accompanying 10-year plan.

While there have been some slight changes in both the near and long-term revenue outlook since the Governor’s proposed budget was published, there have been some potentially significant changes already on the spending side, in particular with the passage by both houses of the Legislature of SB 140, the proposed $241 million increase in K-12 spending, currently sitting on the Governor’s desk for signature, enactment through lack of signature, or veto.

Last week, Alexi Painter, the head of the Legislative Finance Division (LFD), briefed the Senate Finance Committee on the impact on the FY25 budget of SB 140 and some other legislation working its way through the Legislature. While that impact – and the potential implications for the FY25 Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) – were startling enough, the longer-term implications of what is happening this session on the spending side of the budget are of even more significant concern.

The purpose of this week’s column is to quantify those longer-term implications, which were left unaddressed in the LFD’s presentation.

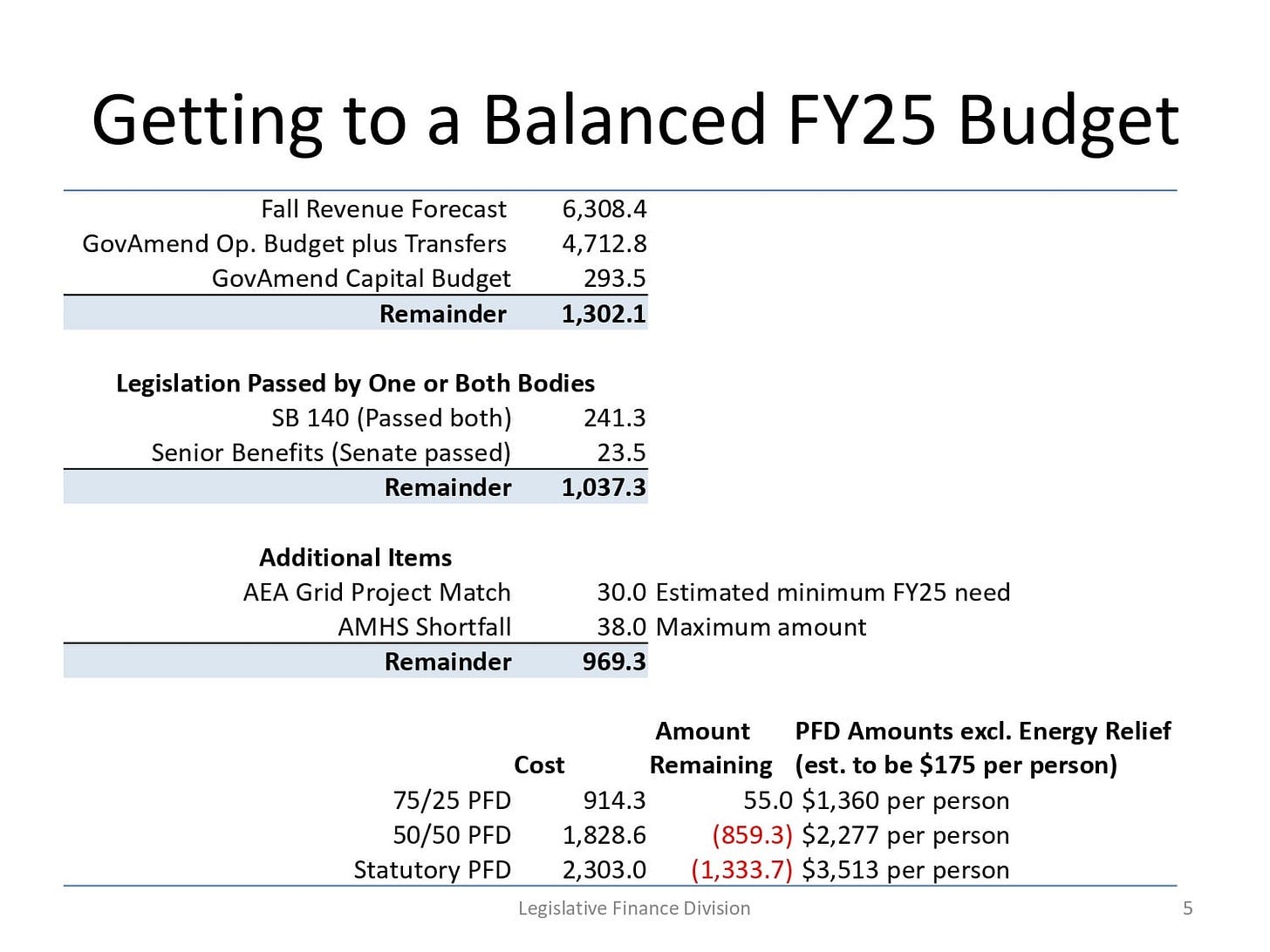

We start with the items reflected on Slide 5 of LFD’s presentation.

The purpose of that slide was to update the Governor’s proposed FY25 budget for the impact of some of the spending legislation already passed so far this session by one or both bodies, as well as some additional items that LFD projects will likely be added during the ongoing budget process.

The slide also showed the status of the budget at various PFD levels, assuming the additional spending but the adoption of no additional revenues to pay for it.

Interestingly, the slide only incorporated some of the spending legislation that has already passed one or both bodies. The slide did not include any consideration of SB 88, the bill to revert Alaska’s state pension system to a defined benefits approach which passed the Senate in January, nor HB 89, Representative Julie Coloumbe’s (R – Anchorage) bill to increase state subsidies for child care, that passed the House the day before LFD’s presentation.

But even without including those the items on the chart already paint a bleak, long-term fiscal outlook for the state.

Each Friday, we publish an update of the current long-term budget outlook. We calculate revenues using the most recent long-term income and earnings projections published by the Permanent Fund Corporation and a long-term projection of traditional revenues based on current oil futures. On the spending side, we have been using without modification the “baseline” numbers included in LFD’s “Overview of the Governor’s [FY25 Budget] Request.”

Here’s the most recent update at the time we are writing this column:

As noted in the two far right-had columns in the yellow highlighted area, the current law deficits facing Alaska already average $1.12 billion per year over the first five years and $1.41 billion per year over the full 10-year period.

At those levels, the deficits already equal roughly 21% and 25%, respectively, of total spending and represent roughly 3.5% and 4.3%, respectively, of total resident and non-resident adjusted gross income.

That’s the baseline fiscal outlook that Alaska is already facing.

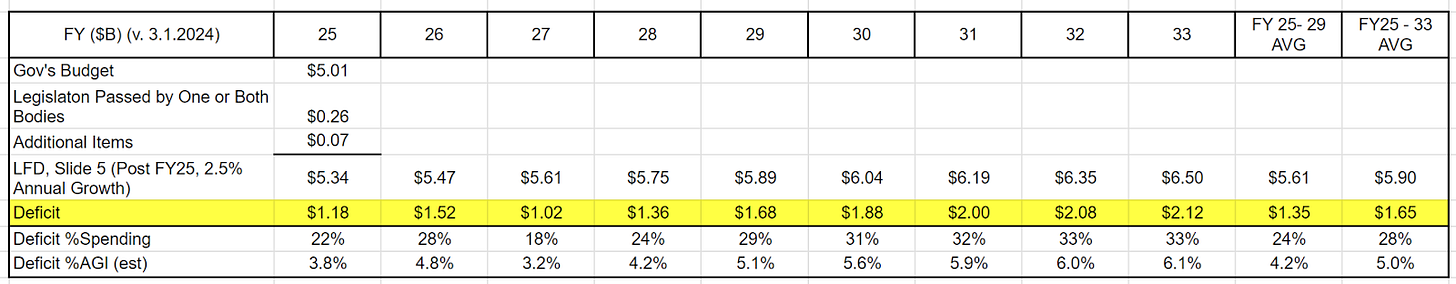

Now, here’s the same chart using the same current revenues but updating projected FY25 spending for the items included on Slide 5 of LFD’s presentation and thereafter escalating spending over the remainder of the 10-year period at the same overall 2.5% per year used in LFD’s previous baseline.

The consequences are that the current law deficits jump by 20% to an average of $1.35 billion per year over the first five years and by 17% to an average of $1.65 billion annually over the full 10-year period.

Deficits reach 24% and 28%, respectively, of total spending and 4.2% and 5%, respectively, of total resident and non-resident adjusted gross income.

LFD’s presentation did not stop there, however. On the subsequent two pages, it projected the cost of various other proposals, such as increased capital spending for renewable energy, school construction, and school major maintenance (Slide 6), and the cost, among other things, of Governor Dunleavy’s proposed “Alaska Affordability Act” and teacher bonus programs (Slide 7).

Here are the items and the amounts:

Given the size of deferred maintenance, the potential for increased spending from these lists alone is almost infinite. For purposes of estimating the impact, however, we assumed an additional $250 million in annual spending resulting from some combination of the items on these slides plus the unstated costs of the return to defined benefits and Rep. Coloumbe’s HB 89.

Here’s the result:

The current law deficits jump by an additional 19% over the Slide 5 analysis to an average of $1.61 billion per year over the first five years and by an additional 17% to an average of $1.93 billion per year over the full 10-year period.

Combined, the impact of the two increments (Slide 5 and Slides 6 and 7) raises annual average current law deficits by 44% over the next five years and 37% over the full 10-year period.

Deficits reach 27% and 31%, respectively, of total spending and 5% and 5.8%, respectively, of total resident and non-resident adjusted gross income.

What is already a bleak fiscal situation becomes much, much worse.

What is the impact on PFD levels? Nothing if the increased spending is paid for through other, more equitable means and the PFD is distributed either according to current law or as a percent of the Legislature’s “percent of market value” (POMV) draw from the Permanent Fund.

But the impact will be huge if, as the Legislature has continued to do for the past seven years and LFD’s presentation implies, the increased spending is paid for entirely through additional cuts in – or as University of Alaska – Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) Professor Matthew Berman puts it, taxes on – the PFD.

Here are the projected amounts available for distribution as a PFD under the various approaches:

If either the current statutory approach or the POMV 50/50 approach is used, the average annual amounts will remain, on average, at or near $2 billion over the next five years and for the 10-year period as a whole.

The average annual amounts are cut roughly in half, to at or near $1 billion on average over both the next five years and for the 10-year period as a whole if either the POMV 25/75 approach is used or, using a “leftover” approach spending is held to the levels reflected in either LFD’s baseline or, to a lesser extent, the Slide 5 levels.

However, if spending rises further to the levels reflected in Slides 6 and 7, the average annual amounts plunge to roughly $720 million over the next five years and $630 million over the 10-year period if a “leftover” approach is used.

Viewed differently, here is the level of the PFD as a percent of the POMV level under each of the “leftover” scenarios.

The PFD level plunges below 25% of the POMV (i.e., below POMV 25/75) under all of the scenarios during the 10-year period. That occurs by FY32 under the “Baseline” scenario, by FY28 under the “Slide 5” scenario, and immediately (FY25) under the “Slide 6 & 7” analysis.

Put another way, by the end of the 10-year period, the PFD is already on track to fall to 24% of the POMV under the “Baseline” scenario, but as a result of the additional measures under consideration by this Legislature, will fall to 18% under the “Slide 5” scenario, and to just 11% of the POMV draw under the “Slide 6 & 7” scenario.

Who pays for the increased spending?

As we’ve repeatedly explained in previous columns, if the increased spending is paid for by using PFD cuts, middle and lower-income – 80% of – Alaska families will bear the brunt of the costs.

Every income bracket and racial and age demographic – particularly including Alaska Natives – other than those in the top 20% and non-residents will experience deeper income cuts than the average impact.

As we explained most recently in last week’s column, by contributing more than the average, those families will be used effectively to subsidize the impact of the increased spending on those in the top 20%, who will contribute significantly less than the average, and non-residents, who will contribute zero toward government costs.

The result is that the top 20% and non-residents will come out relatively unaffected by the increased costs, while middle and lower-income Alaska families fall even further behind. The income gap between the two – already significant to the Alaska economy – will continue to grow.

Put another way, Alaska will remain a tax haven for non-residents and those in the top 20%, but the most-regressive-in-the-nation sinkhole for middle and lower-income – i.e., the remaining 80% – of Alaska families.

That is where this Legislature is leading Alaska.

The Legislature could partly offset that effect by, at least, raising the revenue required to pay for FY25 and future increased spending through more equitable approaches than continued PFD cuts. While that would not be sufficient to fully reverse the adverse impact of the continuation of past cuts, at least it would avoid digging the current hole facing middle and lower-income Alaska families, particularly working-age middle and lower-income Alaska families, even deeper.

But we don’t hold out much hope that this Legislature, whose members largely live in a much different economic bubble than middle and lower-income Alaska families, are prepared to take that step. That likely will be a step left, if taken at all, for future legislatures.