The Friday Alaska Landmine column: Why has the Department of Revenue stopped helping Alaskans understand their fiscal options?

DOR was providing Alaskans the ability to understand the impact of various fiscal options, then just as the state is staring at the fiscal wall dead ahead, DOR has stopped. Why?

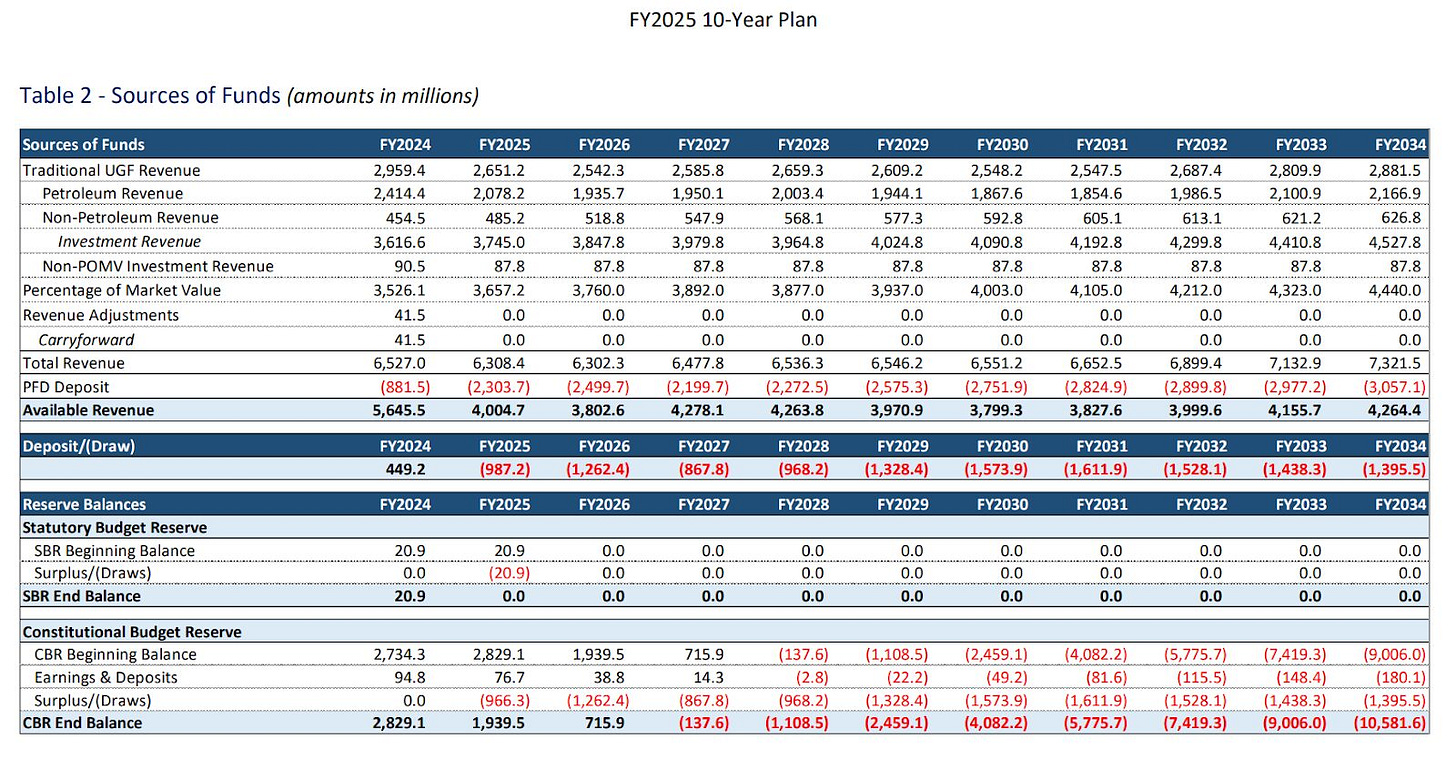

As we explained in our column two weeks ago and as even Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) own 10-year fiscal plan projects, Alaska is just three short fiscal years away, at most, from hitting the fiscal wall many have been predicting would occur at some point since the state first started down the path of deficit spending in the early 2010s.

The Dunleavy 10-year plan clearly tells the story.

After two more years of draws in Fiscal Years (FY) 2025 and 2026, the Constitutional Budget Reserve (CBR), the state’s last-remaining “rainy day” fund, runs dry. In FY 2027, there isn’t enough in it completely to offset the anticipated deficit the state runs for that year. After that, there is nothing remaining in the tank to offset a continuous run of deficits.

Actually, we think the Governor’s 10-year plan represents an overly optimistic case. Substituting the Legislative Finance Division’s (LegFin) most recent projected spending levels for the politically convenient but unrealistically low levels used in the Governor’s 10-year plan and oil revenues derived from current futures market prices for those projected by the administration, we believe the CBR will run dry one year earlier, in the course of FY 2026.

But whether the state’s collision with the wall is two years away or three really doesn’t matter for purposes of this week’s column. The point is that it is imminent.

As we explained in our previous column, what is most surprising – indeed, shocking – about the Governor’s budget and 10-year plan is that he fails to offer any plan for avoiding the impending collision. As we said in that column, we believe the failure blatantly violates AS 37.07.020(b)(2), which requires that the 10-year plans submitted by the governor “must balance sources and uses of funds held while providing for essential state services and protecting the economic stability of the state.”

As is clear, past FY 2026, the Governor’s most recent 10-year plan fails to propose any sources of funds that balance the proposed uses. Instead, it just artificially drives an already empty CBR deeper and deeper into the red.

But in our view, responsibility for the failure to help prepare a plan to avoid the collision is also shared by the Department of Revenue (DOR) and its current Commissioner, Adam Crum.

While it likely wasn’t her favorite thing to do, two years ago, when the Legislature last made its own serious run at crafting a balanced fiscal plan to avoid the coming collision, then-Commissioner of Revenue Lucinda Mahoney stepped up to the plate over the course of two hearings (August 5, 2021, and August 10, 2021) to outline a number of options, with estimates, for raising the revenue needed to avoid the collision.

While it didn’t include every option others had studied – Commissioner Mahoney specifically declined to discuss an income tax, for example, and it didn’t include the flat tax we have advocated – it included a broad range which, combined, was sufficient to close the then anticipated deficits. This slide outlined the options, which subsequently were explained in greater detail in appendices to the Commissioner’s slide deck:

Following that presentation, in connection with the Fall 2021 Revenue Sources Book, DOR then published a “Fiscal Plan Model (v1 20211103),” which, as described by Commissioner Mahoney in her earlier testimony, was intended to serve as “a collaborative tool for all to use … to design your own solution with your assumptions.”

The model lived up to that objective, providing both legislators and the public with the ability to change both existing fiscal factors, such as state spending and Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) levels, as well as introduce new ones, such as the oil tax changes and the state sales tax and gambling proposals that had been at the heart of Commissioner Mahoney’s earlier testimony.

The model reflected those options by providing users with a way to include them in building their “own solution” by toggling them in through the following menu:

That menu, which enabled both Alaskans and legislators to develop and push their own fiscal plans, was largely repeated again in the DOR Fiscal Plan Model included with the Spring 2022 Revenue Forecast (Spring v 1 20220411).

Then, after Commissioner Mahoney resigned and Adam Crum became Commissioner, it essentially disappeared. There was no update to the Fiscal Plan Model included with the Fall 2022 Revenue Sources Book. When an update finally did appear in connection with the Spring 2023 Revenue Forecast (Spring 2023 v 1 20230410), the additional options were gone.

The most recent version, published in connection with the Fall 2023 Revenue Sources Book, is the same on this point as that included with the Spring 2023 Revenue Forecast. Alaskans are kept in the dark about the various options and their impact.

The result, again, is that the only options presented are either spending cuts or PFD cuts.

That, essentially, is no choice at all. After its failed effort to push and sustain deep spending cuts in its initial FY 2020 budget, the Dunleavy administration has not tried again since. That means in its most recent, Crum-era “Fiscal Plan Models,” the only option DOR realistically is offering for Alaskans to consider are deep and continued PFD cuts.

That conflicts with what Governor Dunleavy has said elsewhere is his objective. As we have explained in previous columns, PFD cuts push the burden of balancing the budget almost entirely to middle- and lower-income Alaskan families. Indeed, as researchers at the University of Alaska-Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) concluded in a 2017 study, of all of the various revenue options, “[a] cut in PFDs would be by far the costliest measure for Alaska families.”

Our previous look at the impact of using PFD cuts in the FY24 budget by income bracket makes the point clear:

On average, using PFD cuts, the FY24 budget diverts roughly 3.6% of total adjusted Alaska gross income (including the estimated portion received by non-residents) to government. But that burden is distributed hugely disproportionately. Non-residents receiving Alaska-sourced income contribute nothing. Compared to an average burden of 3.6% of adjusted gross income, those in the top 20% only contribute roughly 2.2%.

On the other hand, on average, middle-income Alaska families are required to contribute roughly 6.7% of their adjusted gross income, and more than 19% is diverted from the income of those in the lowest 20% income bracket.

In a press conference earlier this year, Governor Dunleavy said about a fiscal plan, “a broad-based solution that doesn’t gouge or take huge parts from one sector (of Alaska) or another, or penalize one sector for another is probably the most important thing we can do.”

An approach that, of the various revenue options, is “by far the costliest measure for Alaska families” and takes more than 6% and 19% of adjusted gross income from middle- and lower-income Alaska families, respectively, while taking much less from families in the top 20% and none from non-residents, certainly doesn’t meet that standard.

Instead, if anything, it is the poster child for an approach that “gouges or take(s) huge parts from one sector or another, or penalize(s) one sector or another.”

Certainly, the Crum-era DOR isn’t alone in targeting PFD cuts as the solution.

For example, rather than include PFD cuts as one from a list of options as both the previous 2016 ISER and 2017 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) studies for the Legislature do, an online “poll” currently being promoted by Commonwealth North similarly targets PFD cuts as the preferred solution by treating the option as the starting point of any analysis (“You will start by deciding how much should be spent on Permanent Fund dividends; this choice will determine the amount of spending increases or cuts needed to balance your budget.”)

But at least Commonwealth North ultimately demonstrates some intellectual honesty by going on from there to include other options. DOR’s Crum-era “Fiscal Plan Model” doesn’t do even that.

Why has the Crum-era DOR limited the options included in its Fiscal Plan Model? One can speculate it is because of the Commissioner’s well-known, close ties to oil-industry and other lobbyists and their desire to keep Alaskans from seeing information about the potential additional revenue available from relatively minor adjustments in oil taxes or through other approaches that might require contributions toward the solution from non-residents, those in the top 20% or others, other than middle- and lower-income Alaskan families.

But regardless of the reason, the impact is to deprive legislators and other Alaskans of highly useful information at a particularly critical time in Alaska’s history.

One more time, even under Governor Dunleavy’s 10-year plan, Alaska hits the fiscal wall in three years. More realistically, we think it’s two. Either way, Alaska needs to be plotting and implementing a different course now. This is the time to have all of the information relevant to the alternatives on the table in plain sight for all to see. For whatever reason, however, Commissioner Adam Crum’s DOR is keeping some of the most important pieces locked away.