The Friday Alaska Landmine column: Oil taxes are not a silver bullet

Some claim raising oil taxes is all that is needed to address Alaska's current fiscal situation. We explain why it wouldn't even come close.

Last week’s column focused on the fiscal condition in which this Legislature is leaving the state. Our point was that, as a result of the substantial growth in spending this Legislature has authorized, the state is facing significant financial challenges in the years ahead. We articulated that in terms of the potential level of cuts in the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) that may be required to balance future budgets and in the effective average and distributional tax rates those cuts would represent on Alaska personal income. Both are significant.

One response to the column caught our attention because it reflected what we often hear when discussing these issues. The comment was that we shouldn’t be concerned about spending or deficit levels because, in the commentator’s opinion, eliminating “the $8/bbl … oil tax credit” alone would balance the budget with money to spare (“This adds up to 1.6 Billion dollars that the State of Alaska is failing to collect for Alaska’s oil every year which is precisely why Alaska’s revenue is 1.5 Billion dollars low.”). More broadly, we often hear that increasing oil taxes in various ways is all that is required to balance future budgets and return to statutorily-driven PFD distributions.

But neither the specific comment we received in response to last week’s column nor the more generalized “just tax the oil companies more, and all will be well again” approach is accurate.

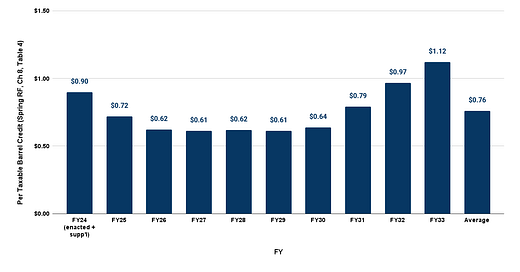

The Department of Revenue projects the annual impact of the per barrel oil tax credits and other aspects of oil taxes twice a year as part of the Fall and Spring revenue forecasts. The most recent projection of the per barrel tax credits is reflected in this year’s Spring Revenue Forecast in Chapter 8, Table 4, line 11. The credits never reach “$1.5 billion” per year or anything close to that amount. The highest level is the projection for FY33, nine years from now, at $1.12 billion. The average over the period is $760 million, roughly half of that estimated by the commentator.

Moreover, given the increases resulting from the recent Legislature’s actions, the current law deficits over the period—or, as the commentator put it, the amounts by which Alaska’s revenue is “low”—are higher than $1.5 billion. As we explained in last week’s column, while they start out lower than that amount, by the end of the forecast period, the current law deficits are higher than $2 billion. The average over the period, measured by the projected cut in (tax on) PFDs, is $1.75 billion.

The nominal result using these numbers is that even if the Legislature were to eliminate the entire per barrel credit – and for discussion’s sake, close the “Hilcorp loophole” as well – the state still would be running substantial current law deficits. Here is the result using the level of per barrel credits included in the Spring Revenue Forecast, the most recently estimated amount of the Hilcorp loophole, escalated at inflation, and the level of current law deficits projected in last week’s column.

Averaged over the period, even the combination of eliminating the per barrel oil credits entirely plus closing the Hilcorp loophole would only cut the deficits in half. The remaining deficits – the amount reflected above in the level of the projected PFD cut – would still average $870 million per year, or a projected 2.4% of Alaska Adjusted Gross Income. Eliminating the per barrel tax credits plus closing the Hilcorp loophole wouldn’t raise enough to avoid PFD cuts even in one year over the period.

As a fallback, those who previously argued eliminating the per barrel credits would eliminate all of the deficit may now be telling themselves, “OK, maybe not all, but at least it would reduce the deficit some.”

But that misses the point. Regardless of what happens with oil taxes, Alaskans will still have to bear some of the costs of their government themselves. The deficits are too great to avoid it.

By withholding and diverting to government a portion of the PFDs provided under current law, since 2017, the responsibility for bearing those costs largely has been pushed down to a relatively isolated and politically weak sub-group of Alaskans – middle and lower-income Alaska families. Using that approach has trivialized the share borne by those in the top 20% as well as allowed non-residents receiving a portion of their income from Alaska sources to escape, as former Governor Jay Hammond put it in Diapering the Devil, “scot-free.”

Even eliminating the per-barrel credits entirely would not change that. Under the most favorable outcome, continuing the current approach would result in the sub-group of middle and lower-income Alaska families – and, through them, the overall Alaska economy – still bearing a disproportionately large share of the remaining and still massive $870 million annual average deficit while upper-income Alaska families and non-residents escape unscathed.

And even that result likely represents an unrealistic high-water mark. As we’ve explained in previous columns, there is a point beyond which increasing oil taxes is counterproductive. By depressing continued investment – and with that, production volumes – increasing taxes beyond the so-called “revenue-maximizing point” results in lowering future revenues below those realized at lower tax rates.

As we’ve explained before, while we don’t believe that current oil tax rates are at the “revenue-maximizing point”—and thus there is room for some increase in them—we also believe the evidence is that eliminating all of the per-barrel credits or using other measures substantially to increase tax revenues would push oil taxes past the “revenue-maximizing point” and result in increasingly lower revenues and, thus, higher deficits going forward.

As a consequence, to us, a singular focus on modifying oil taxes is hugely counter-productive. While it may reduce by some, it does not come even close to eliminating a continuing need for raising a significant amount of revenue from Alaska families. Because of the hugely adverse impact of the current approach on middle and lower-income Alaska families and, through them, the overall Alaska economy, pushing for a more equitable, broad-based, and low-impact approach to accomplishing that objective should be the priority.

Taking the eye off that ball to pursue an approach that, at best, covers only half the deficit—and likely less when considering the revenue-maximizing point—focuses attention and resources on a less important target.

In short, we don’t ignore the potential contribution toward an overall fiscal plan that some changes in oil taxes could produce. Both closing the Hilcorp loophole and better adjusting the per-barrel tax credit toward the “revenue-maximizing point” has a role to play. But they should not be the sole or even the primary focus. At best, they address only a part of the problem. Correcting the hugely disproportionate and highly adverse impact of the current regressive fiscal approach should take precedence.

As the Legislature’s 2021 Fiscal Policy Working Group concluded, adjustments to oil taxes should be part of an overall comprehensive and balanced approach. Because they are incapable of solving the problem alone, however, they should not be permitted to suck all of the oxygen from the effort.