The Friday Alaska Landmine column: Alaska's outmigration death spiral

Efforts to address Alaska's outmigration issue through additional government spending will only make the problem worse if the funding comes at the expense of the very families we are trying to retain

Death spiral: a situation that keeps getting worse and that is likely to end badly, with great harm or damage being caused – Cambridge Dictionary

An article in this month’s Alaska Economic Trends (Economic Trends) published by the state’s Department of Labor and Workforce Development (DOL) and a recent follow-up article on it by Alex DeMarban in the Anchorage Daily News captures in numbers what we have begun to think of as a death spiral into which Alaska is slowly sinking.

The article in the December 2024 edition of Economic Trends is titled “Long-term population decline.” The article in the December 4, 2024, edition of the ADN is titled “Alaska could be facing its first long-term decline in population and resulting economic slowdown.” Both report on DOL projections that show a 2% statewide population loss from 2023 to 2050, with even greater losses regionally in the Gulf Coast, Interior, and Southeast regions.

The ADN article also reports on the potential consequences:

Fewer students will be available to fill the state’s public schools and universities. Also, a population decline would continue to constrain the local workforce, requiring businesses to rely on importing workers. The nonresident worker rate is already at its highest point in years, the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development recently said. “A shrinking population would definitely slow the economy,” he [David Howell, the author of the Economic Trends article] said.

While the Economic Trends article focuses on a decline in birth rates as the immediate reason for the overall population decline, economic factors also play a significant role. Jobs are one. As the author of the Economics Trend article was quoted as saying in the ADN article, “Future migration trends could differ, potentially altering the population outlook …. Maybe there will be a big project in mining or oil that requires large numbers of workers to move to Alaska, he said.”

Alaska’s high cost of living is often cited as another.

Some are looking to the state government to help solve both. For example, as a recent follow-up to the economic presentation on the Alaska LNG project makes clear, many view the justification for the proposed Phase I of the project as much as a jobs program as an energy source.

Others are also looking to the state government to solve the high cost of living through various state programs, a couple of which were highlighted in the DOL Commissioner’s opening memorandum to the March 2024 edition of Economic Trends.

A recent column from Larry Persily in the ADN pushes in a different direction, but state spending is still in the lead. Titled “The simple answer to Alaska’s outmigration problem,” Persily argues:

Alaskans need to look at why younger people are not moving to the state as much as they did in years past and address those needs, which include good schools, housing, child care, a strong university system, community services and the parks and recreation activities that younger families seek.

It means a retirement system for public employees who often are paid less than their private-sector counterparts.

Make the state more attractive and they will come. And they will fill the jobs and start businesses.

But we are concerned that, at least under the current approach to state fiscal policy, all of these proposals will only make the economics driving Alaska’s outmigration problem worse, not better. From the perspective of outmigration, they will continue pushing Alaska further into a death spiral, not help it pull out.

The reason is because of how the state pays for its programs and, on its current trajectory, would pay for the additional spending the proposals contemplate. That way is through diverting a significant portion of the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) due under current state law to be distributed to Alaska families instead to government to help pay for the programs.

Why does that approach make the economics driving Alaska’s outmigration problems worse?

The answer is simple. As explained by Professor Matthew Berman of the University of Alaska – Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) in an op-ed last year in the ADN, the effect of that approach is to impose on Alaskans – and only Alaskans – the “most regressive tax ever proposed.” And, within that, the impact falls hardest on middle- and lower-income Alaskan families, which, as we have explained in a previous column, is the very group that is driving the outmigration numbers. As we’ve repeatedly explained in other columns, compared to that, there are other approaches to raising the same amount of revenue that would have a much lower impact on those segments.

In that context, using PFD cuts to fund government instead of broader-based alternatives reduces the income of the very segment of Alaskan families the state is trying to retain and attract. It makes the Alaska cost-of-living differential that segment faces worse, not better. It makes Alaska less economically attractive for families in those segments than more. It deepens the economic hole those families are in, not improves it.

And it’s no small difference. While some seek to trivialize the impact of PFD cuts by saying they are “only” $1500 – $2000, the impact at the family level is larger. According to Census Bureau data, the average number of people per household in Alaska currently is around 2.67. That means, using the calendar year 2025 PFD numbers, the impact of PFD cuts on the average-sized family is $5,172.

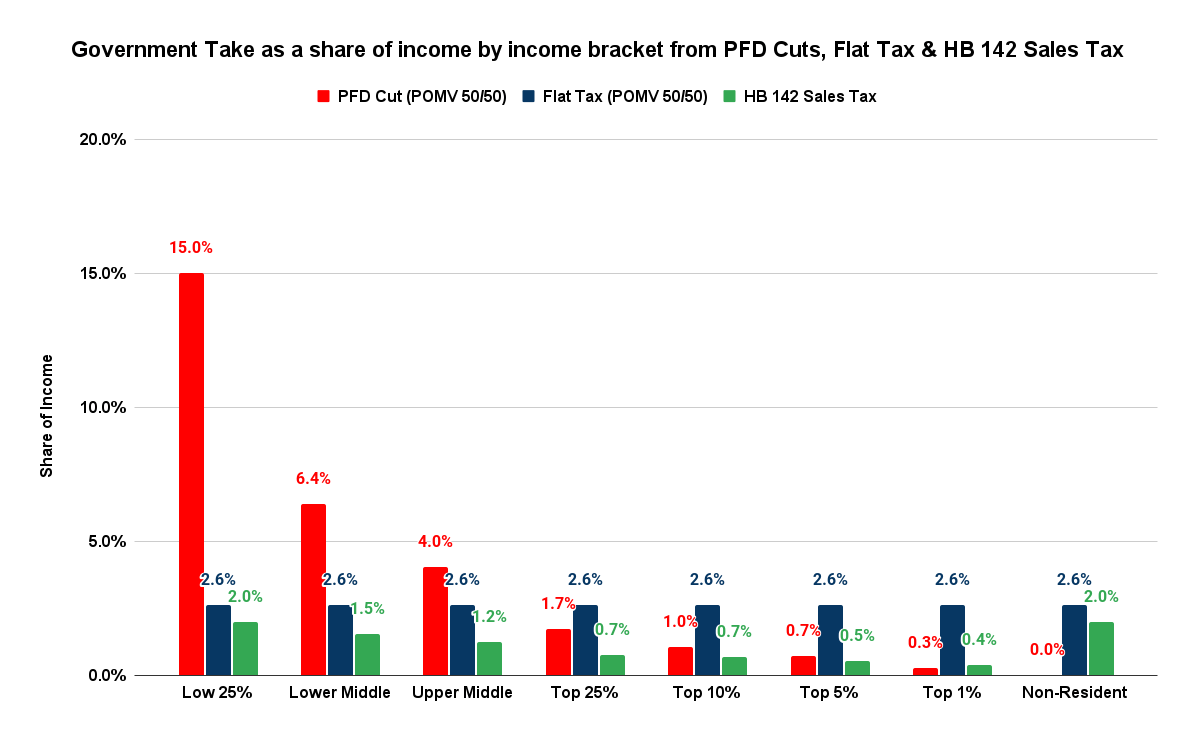

As we have explained in previous columns, the impact of PFD cuts on middle and lower-income Alaska families is significant at that level. Looking at a chart we developed in a previous column, compared to raising the same amount of revenue through a flat tax, on average, PFD cuts take double from middle-income families and nearly six times more from lower-income families. Compared to the ultra broad-based sales tax proposed last session, on average, PFD cuts take nearly four times more from middle-income families and nearly eight times more from lower-income Alaska families.

By taking less from middle and lower-income families, using one of the other alternatives to pay for the costs of government would improve the economics of those groups and, with that, the attractiveness of staying or relocating to the state.

We are not arguing – at least in this column – that the state should not spend the money some have proposed in an effort to increase jobs, reduce the cost side of the cost of living, or in the manner proposed by Persily. That is a discussion for another day.

But we are suggesting that if paid for through PFD cuts instead of other, lower-impact alternatives, the steps will be self-defeating by undermining the economic impact of such measures on the very groups the measures are attempting to retain and attract.

Spending the money certainly will make the contractors and others receiving the funds diverted from the pockets of middle and lower-income Alaska families better off, but it will come at the expense of making the very ones for whose benefit the money purportedly is being spent worse off.

When making the case for the programs, the proponents often say doing so will benefit Alaska overall. If that’s true, all those participating in Alaska, including businesses, non-residents, and oil companies, should contribute to the additional costs, not just middle and lower-income Alaska residents. Doing the latter just continues and deepens the death spiral Alaska is facing.