The Friday Alaska Landmine column: Wait, what? Oil production volumes are projected to grow by a lot, but overall, state revenues from them are dropping

The Dunleavy Administration's Fall revenue projections say oil production is headed up by 35% over the next 10 years, but oil revenues are headed 𝙙𝙤𝙬𝙣 by 13%; what the h*** is going on?

As we noted in our column two weeks ago (“Our first look at Gov. Dunleavy’s FY25 Budget & 10-year Plan: Part 1”), the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) most recent projection of Alaska North Slope (ANS) oil volumes and related revenues in its Fall 2023 Revenue Sources Book (“Fall 23 RSB”) is significantly different than previously projected in its Fall 2022 Revenue Sources Book (“Fall 22 RSB) and Spring 2023 Revenue Forecast (“Spring 23 RF”).

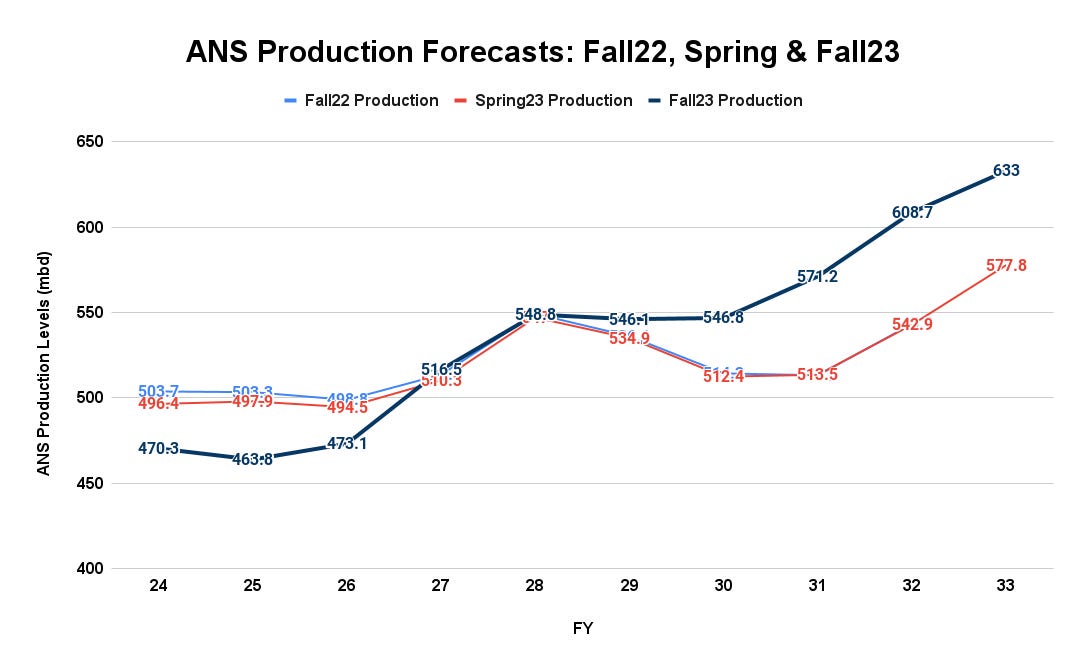

Here are the differences in volumes:

For the first three years, the ANS volumes projected in the latest Fall 23 RSB (dark blue) are significantly lower than those previously projected in the Fall 22 RSB (light blue) and Spring 23 RF (red). The relationship then reverses over the last five years, with the ANS volumes projected in the latest Fall 23 RSB running significantly higher than those projected in the previous two forecasts.

The odd – and concerning – thing, however, is that despite the significant increase in volumes over the period, unrestricted petroleum revenues are projected to head in the opposite direction – downward.

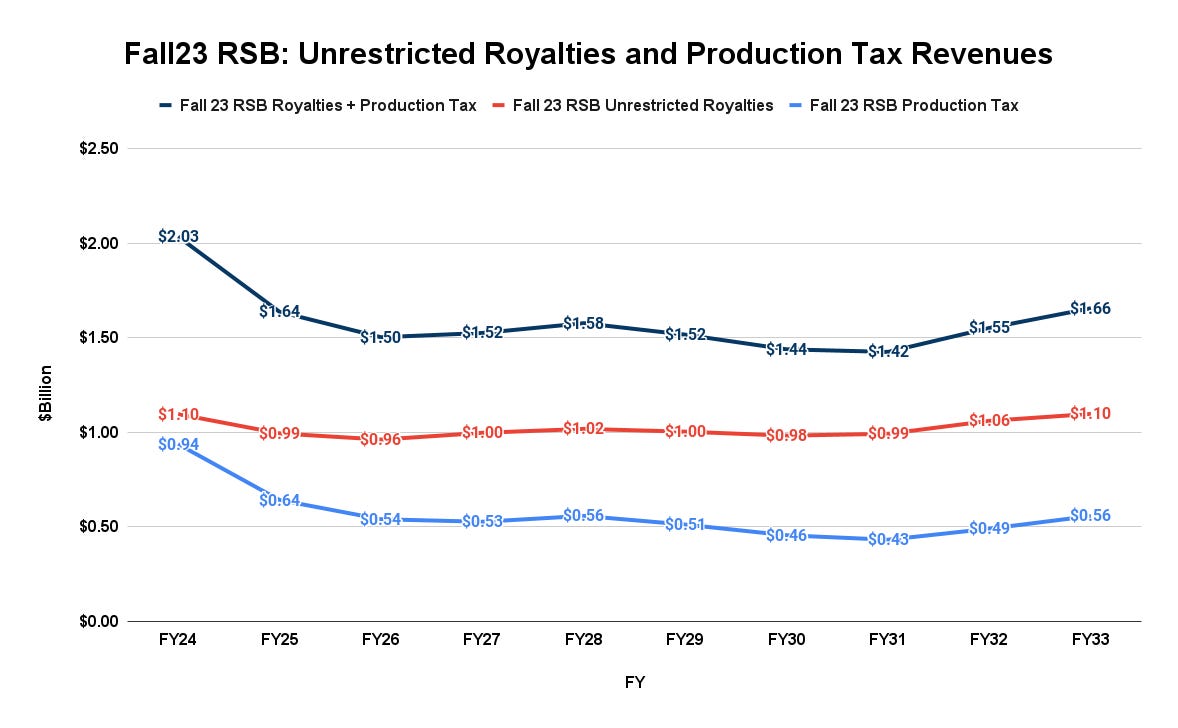

Focusing on the most recent Fall 23 RSB, here is the relationship between volumes and unrestricted petroleum revenues over the period:

While ANS production is projected to rise by more than a third over the period, from 470,000 barrels/day to 633,000 by FY33, unrestricted petroleum revenues actually decline over the same period by nearly 13%, from $2.41 billion in FY24 to $2.10 billion in FY33.

The decline is even greater when focusing on the two components of unrestricted petroleum revenue most directly tied to production: unrestricted royalty revenues and production taxes.

Combined, the components decline over the period by over 18%, from $2.03 billion in FY24 to $1.66 billion in FY33. Almost all of that is due to a decline in production taxes. Unrestricted royalties are both projected to start and end the period at $1.10 billion. On the other hand, production taxes drop over the period by more than 40%, from $940 million in FY24 to $560 million in FY33.

Certainly, some of the difference between the significant increase in oil production levels and the decline in related revenues is due to the decline in oil prices over the period. The Fall 23 RSB projects oil prices to decline over the period by $12/barrel (approximately 15%).

But applying the Department of Revenue’s price sensitivity analyses, even if oil prices remained at the FY24 projected price level of $82/barrel over the entire period, total unrestricted royalties plus production tax revenues still would only increase by a little over 13%, far short of the jump of nearly 35% in production volumes.

Why are the state’s projected oil revenues dropping over the period while production volumes skyrocket?

There appear to be four factors at play. As we just noted, the first appears to be oil prices. The Fall 23 RSB forecast projects oil prices will fall from $82/barrel for FY24 to $70/barrel in FY33. But that only explains part of what is occurring.

The second is that the largest share of the projected production increase over the period comes from federal lands, largely those in the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska (NPRA), which results in royalty revenues for the federal government, but not the state. While overall production volumes are projected to increase by nearly 35% over the period, from 470,000 barrels a day to 633,000, non-NPRA (or largely, state royalty-bearing) volumes are projected only to increase by approximately 11%.

The third is that an increasingly larger share of production is coming from sources that, under the state’s current oil tax code, qualify for a Gross Value Reduction (GVR) in production tax. As explained in the Fall 23 RSB, volumes qualifying for the GVR are entitled to a significant reduction in production tax:

The gross value reduction (GVR) allows a company to exclude 20% or 30% of the gross value for that production from the tax calculation. Qualifying production includes areas surrounding a currently producing area that may not be otherwise commercial to develop, as well as certain new oil pools. Oil that qualifies for this GVR receives a flat $5 Per-Taxable-Barrel Credit rather than the sliding scale credit available for most other North Slope production. As a further incentive, this $5 Per-Taxable-Barrel Credit can be applied to reduce tax liability below the minimum tax floor assuming that the producer does not seek to apply any sliding scale credit. The GVR is only available for the first seven years of production and ends early if ANS prices exceed $70 per barrel for any three years.

According to the Fall 23 RSB, GVR volumes are projected to increase substantially over the next ten years, up from only 24,600 (5% of total volumes) in FY24 to 166,000 (26%) by FY33. Because of their highly favorable tax treatment, growth in GVR volumes contributes only marginally to overall production tax revenues.

At the end of the period, there is some indication that the GVR-related impact is starting to decline. But that does not necessarily translate into good news for state revenues overall.

At the same time, the Fall 23 RSB projects that per-barrel production tax credits – which at projected oil price levels are largest for non-GVR volumes and are projected to decline significantly from the FY24 level through most of the period – will again begin to grow, ending the period at a level roughly 18% higher than where they began.

Recall that at the same point, total unrestricted petroleum revenues are still down by 13% over FY24 levels, combined unrestricted royalty and production tax revenue are still down by over 18%, and production tax revenues alone are still down by over 40%. That may indicate that the benefit to state revenues from the decline in GVR volumes ends up being offset (and potentially more than offset) by commensurate growth in per-barrel production tax credits and other factors.

The fourth factor pushing down oil revenues also relates to how production taxes are calculated. Even though DOR projects oil prices to fall by nearly 15% over the period from FY24 to FY33, annual “Allowable Lease Expenditures,” which are deductible from each company’s overall production tax base, are projected still to increase by approximately 5% over the period, from $6.18 billion in FY24 to $6.51 billion in FY33.

Even if oil prices remained constant over the period, the increase in allowable expenditures would still tend to drive down production tax revenues. Because of Alaska’s net profits tax system, the fact that the allowable expenditures are increasing as prices are falling makes the increase in allowable expenditures even more significant.

Combined, these developments call into question one of the basic, long-time tenets of Alaska policy dogma. As Governor Mike Dunleavy (R – Alaska) recently argued in his press conference announcing his FY25 budget, many believe that policies that lead to increased oil production are good for the state because of their positive impact not only on the overall Alaska economy but also on state revenues. (Dunleavy: “If we were allowed to develop every play we have, every oil play we have, every gas play we have, every mining play we have, every timber play we have, our revenue would be double, triple what it is today.”)

But the Fall 2023 RSB shows that even with oil production volumes projected to climb by 35% over the next ten years, unrestricted state revenues from that production are projected to fall by approximately 13%.

As the saying goes, with friends like that, who needs enemies? Under the current oil tax code, the circumstances surrounding the dramatic increase in oil production volumes are causing state revenues to fall, not increase, nor even stay level.