The Friday Alaska Landmine column: Comparing price projections

The recent price projections offered in support of the Alaska LNG Phase I project raise some significant issues about the proposal. We explain what they are here.

Earlier this month, the House Resources Committee held a hearing to receive updates on both the Cook Inlet gas issue and the Alaska LNG project. The portion on the Alaska LNG project focused on the project’s proposed “Phase I,” a proposal to build a portion of the proposed pipeline to deliver gas from the North Slope to Fairbanks and Southcentral.

The hearing didn’t receive much local press. The only local coverage we recall seeing at the time was an article in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

But the hearing serves as an important waypoint on the road to next year’s legislative session, during which the Alaska LNG project necessarily will push for continued funding of its efforts, and we anticipate some will push to revive various pieces of Cook Inlet-related legislation that failed to pass during last year’s session. As the proposals have matured, the hearing provided significant insight into how the proponents view the issues facing their projects.

While we will likely have much more to say on the issues as the discussions continue during the session, at this point, we want to focus on a couple of the delivered price projections discussed during the hearing. Much of the hearing was spent on efforts by the proponents of the Alaska LNG and Cook Inlet projects to convince listeners that their project would result in prices at least in the same range as, if not lower than, the third alternative, importing liquified natural gas into the Cook Inlet from other sources.

But some of the projections they offered have significant issues.

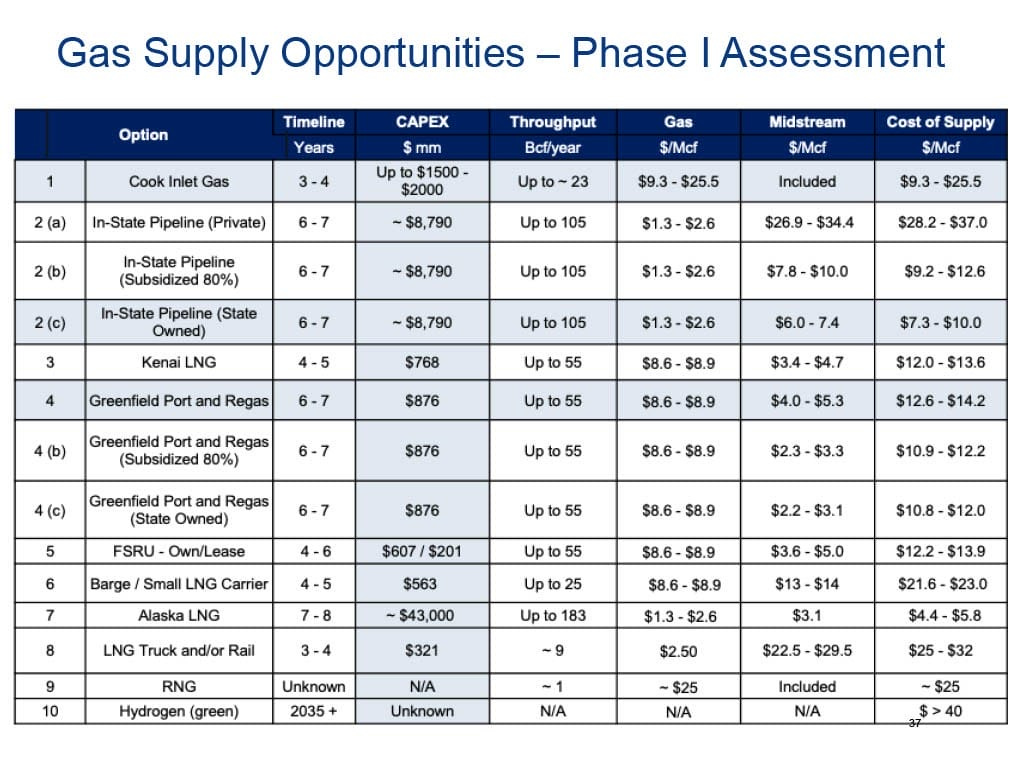

This is not the first time the Committee has heard delivered price projections for the various alternatives. At a joint hearing with the Senate Resources Committee last February, Enstar President John Sims presented a slide that reflected price projections for the various alternatives evaluated in the course of the 2023 “Cook Inlet Gas Supply Project Phase I Assessment” prepared by consultant BRG (BRG study) for various Southcentral utilities. Here is the slide:

What is now called the Alaska LNG “Phase I” proposal was reflected in the BRG study as Options numbered 2(a), 2(b), and 2(c), various alternatives for developing an “In-State Pipeline.” There, the study estimated delivered prices – what the study called “Cost of Supply” – for three alternatives: a privately owned (non-subsidized) pipeline, a second which is 80% subsidized, and a third which is “state-owned,” or fully subsidized.

Prices delivered under the three alternatives were significantly different. In the BRG study, the delivered price for the “private” (unsubsidized) alternative was between $28.20 and $37/mcf (thousand cubic feet), the “80% subsidized” delivered price was between $10.90 and $12.20/mcf, and the “state owned” (fully subsidized) delivered price was between $7.30 and $10.00/mcf.

Importantly, for purposes of this comparison, the delivered prices for the pipeline options in the BRG study were based on an assumed capital cost of $8.790 billion, significantly (23%) less than the $10.769 billion capital cost on which the prices presented at this month’s hearing as part of consultant Wood Mackenzie’s analysis of the Alaska LNG Phase I (Wood Mackenzie study) are based. The BRG study was also based on a gas cost component of $1.30 – $2.60/mcf, higher than the $1/mcf price assumed in the Wood Mackenzie study.

The delivered prices in the Wood Mackenzie study for the Phase I project aren’t presented similarly. Instead of being categorized as “private,” “80% subsidized,” and “state owned” (fully subsidized), the delivered prices in the Wood Mackenzie study are based on volumes.

As reflected on the following slide, the Wood Mackenzie study calculates the delivered prices for four cases: “Baseload” (current demand levels plus Fairbanks and some increased demand at the Nikiski Refinery), “WM Case” (baseload plus some additional industrial demand), “Additional Industrial” (WM Case plus some additional demand on top of that), and “Alaska LNG” (full international or equivalent deliveries).

The projected delivered price under the “Baseload” case is $12.80/mmbtu (million British thermal units, roughly the equivalent of an mcf), under the “WM Case” is $11.20/mmbtu, under the “Additional Industrial” case, is $8.97/mmbtu, and under the “Alaska LNG” case, is $2.23/mmbtu.

At first blush, the prices in the two studies do not appear to be directly comparable because of the differences in capital and gas costs. But the studies contain enough information that, with some calculations, the prices can be restated on a comparable base. Here is the result:

The first adjustment is to restate the options in the BRG study on the same gas cost as reflected in the Wood Mackenzie study. We do that by subtracting from the prices in the BRG study the difference between the costs of gas included in the BRG study and the $1/mmbtu reflected in the Wood Mackenzie study.

The second adjustment is to restate the options in the BRG study based on the same projected capital cost as reflected in the Wood Mackenzie study. We can make that adjustment because the Wood Mackenzie study contains a “sensitivity” analysis that shows the impact on the delivered price of increased or decreased costs in various categories. We apply the “Capex Sensitivity” included in the analysis to scale up the prices included in the BRG analysis for the 23% difference in capital costs between the two approaches.

The third adjustment is to restate the delivered prices in the BRG study for the different volume cases included in the Wood Mackenzie study. The BRG study is based on volumes in the same range as Wood Mackenzie’s “Baseload” case. We adjust the price ranges included for the options in the BRG study, previously adjusted for gas and capital costs, for the higher volume cases using the same ratio as the prices in the higher volume cases in the Wood Mackenzie study bear to the price in its “Baseload” case.

The results reveal something that neither the presentation before the Committee by Wood Mackenzie nor the follow-on presentation by the Alaska Gasline Development Corporation discussed. That is that the delivered prices included in the Wood Mackenzie analysis for the Alaska LNG Phase I project appear to rely heavily on significant state subsidies. Indeed, the delivered prices they project consistently fall in the range of those in the BRG “80% subsidized” case.

Digging into the “sensitivity” analysis included in the Wood Mackenzie presentation, we can identify and calculate the impact of at least a couple of those subsidies. One is the impact of cutting the 2.0% property tax rate generally applicable to pipelines in the state by 90% to the 0.2% property tax rate used to calculate the delivered prices in the Wood Mackenzie study. A second is the impact of lowering the return on equity from 12.5%, which is generally consistent with current financial market conditions, to the below-market 10% assumed in the Wood Mackenzie study.

Likely, the only way a lower-than-market rate return on equity can be achieved is by using cuts in the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) to fund the equity, as proposed by Representative Jesse Sumner (R – Wasilla) in his House Bill 222 or directing that the equity come otherwise from state funds invested through a state entity, such as the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA) or the Alaska Permanent Fund. It is highly unlikely a private investor would accept a similar below-market return on the investment.

The combined effect of eliminating both subsidies would be to raise the $11.20/mmbtu price for the WM Case to $14.51/mmbtu. There likely are more subsidies embedded in the projection, however, because even at that higher price level, the projected price is still significantly below the range reflected in the BRG study for the “private” (i.e., non-subsidized) option.

Knowing what types and how much of a subsidy is embedded in the various proposed projects is important. Subsidies created by various forms of cost relief are just another way of charging a portion of the delivered costs to Alaskans, albeit a different set of Alaskans than those served by the Fairbanks and Southcentral utilities who would receive the gas. Where the subsidy comes from the state treasury, in terms of foregone revenues or direct subsidies in the form of below-market investments or loans, those bearing the costs ultimately are those who serve as the marginal source of state revenue. In recent times, that has been middle and lower-income Alaska families through reductions in (taxes on) the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD).

One way or another, the subsidies would likely come out of their pockets.

Subsidies also serve to undermine the “socio-economic” benefits of the Alaska LNG Phase I project, as claimed in the latter part of the Wood Mackenzie presentation. If the claimed benefits are being funded in substantial part through subsidies paid for by others, all that the “benefits” are is income redistribution from one group of Alaskans – those funding the subsidies – to those who benefit from the pipeline. Because those who would benefit from the pipeline include a substantial number of non-residents, such as non-resident materials providers, contractors, and construction workers, it is conceivable that rigorously accounting for the impact of the subsidies could result not only in eliminating the claimed “socio-economic” difference between the Alaska LNG Phase I project and imported LNG, but in actually reversing it.

In other words, rather than attracting new money into the state as would occur in a private, non-subsidized effort, by providing an avenue for bleeding money out of the state, a heavily subsidized project could actually result in net negative “socio-economic” effects.

To understand the consequences of what is being proposed, Alaskans should know the total cost of each alternative, including the embedded subsidies they may be required to pay and who will actually benefit from the construction of the pipeline.

The reason for embedding subsidies in the project appears to be to make the Alaska LNG Phase I project seem more competitive with the cost of imported LNG. The Wood Mackenzie study claims that the prices between the two options are comparable, or indeed even that the Alaska LNG Phase I project results in somewhat lower costs.

But that is true only when comparing the heavily subsidized delivered prices of the Alaska LNG Phase I project assumed in the Wood Mackenzie analysis against the projected unsubsidized prices of imported LNG. Comparing each project’s unsubsidized costs, it is clear that imported LNG is far less expensive for Alaskans.

Moreover, it is not clear that even at the heavily subsidized rates included in the Wood Mackenzie study, the Alaska LNG Phase I project remains competitive.

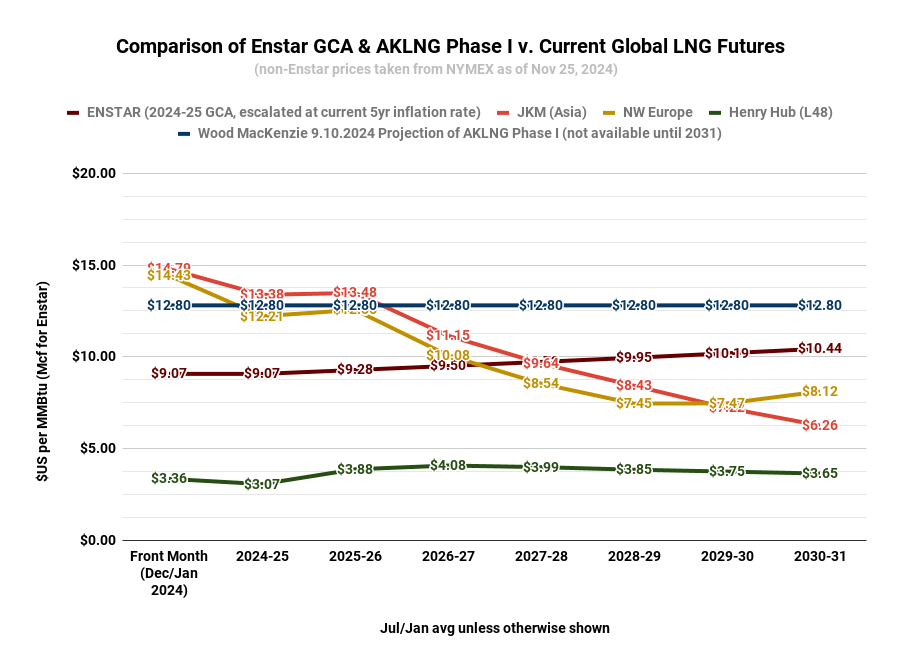

Some readers may recall that, as part of our regular weekly chart series, on Mondays, we publish an analysis of projected global LNG prices as measured in the futures markets, compared to Enstar’s cost of gas and, more recently, the projected delivered cost of gas for the “Baseload” case from the Alaska LNG Phase I project. This is the most recent Monday chart as of the time we are writing this week’s column.

Looking at the far right side of the chart, covering the time period during which, if built, the Alaska LNG Phase I project would be projected to commence deliveries, it is clear that the current futures market is projecting delivered LNG prices in the Pacific market (represented by the “JKM” marker in red) at levels far lower than those projected for the “Baseload case” of the Alaska LNG Phase I project ($12.80/mmtu, in blue). Indeed, the prices for that period in the JKM futures market are lower than even those for the Alaska LNG Phase I “WM” ($11.20/mmbtu) and “Additional Industrial” ($8.97/mmbtu) cases.

The Alaska LNG Phase I project would find it difficult to compete with imported LNG prices at those levels. Compared to other LNG projects, much of the price of the Alaska LNG Phase I project is driven by fixed costs. It isn’t well positioned to match the competitive impact of continued drops in the commodity prices paid by other projects.

It is possible that, if the circumstances were to play out in that manner, by pursuing the Alaska LNG Phase I project, Alaskans could be stuck with gas prices far higher than what they would have paid by pursuing imported LNG, turning the Alaska LNG Phase I project into an energy white elephant. Rather than an economic boon, the project instead could become an inescapable economic albatross, particularly if built with public money the state is counting on to produce significant returns.

We are not suggesting that will happen, but the current numbers indicate a significant risk that it could. And once built, it’s not a risk the state could avoid. The money would literally be sunk into the ground and unavailable for conversion to other assets or projects.

As we said at the start of this column, we will likely have much more to say on this issue as the discussions on these projects continue during the session. For now, we merely want to suggest that the issues are much more complicated and the risks much more significant than some have summarized.